Daughters of the Bamboo Grove tells the moving story of the reunification of two identical twins, the cultural divide between them as a result of the forced adoption of one twin by Chinese authorities, and the effects of the separation on both girls and on their families.

This book presents a vivid and painful window into China’s more recent history during the one-child policy era, which felt like a continuation of the history I’d recently read in Wild Swans by Jung Chang. Reading the accounts of women being held down for forced abortions and, most shockingly, the injection of formaldehyde into full-term babies heads during birth were gut-wrenching and a stark reminder of the immense human cost behind some of the communist party’s darkest policies.

I appreciated how Demick critiqued the common Western framing of Chinese families as simply throwing away daughters. The reality is far more complex, some daughters were stolen outright, others were hidden through informal adoptions within families, making the picture much less clear-cut. The large fines for keeping a second child was an expense that many poor rural families could not afford. That said, Demick didn’t shy away from acknowledging the deep-rooted cultural preference for sons. There are many daughters in China whose given names are Zhaodi which literally translates to ‘beckoning for a younger brother.’ The point was made sharply that if sons had been stolen in the same way, there would have been swift and fierce action to recover them. However, at the heart of the story are two girls, twin sisters Esther and Shuangjie, separated by trafficking and adoption, whose lives unfold on very different continents. While Demick clearly did an enormous amount of investigative work and the story she tells is important, I found myself questioning whether she was the best person to tell it. The book is written through her journalistic lens and sometimes, she seems to presume she knows how the people involved felt, rather than letting them fully speak for themselves.

Demick’s role feels complicated. While she wanted to protect Esther, who had been trafficked and adopted by an American family, she effectively left the decision of if and when to reconnect in the hands of the adoptive family. Even though Demick uncovered the truth when Esther was just 8, it took nearly a decade before the two families were allowed to reconnect. Those lost years could have been crucial for Esther to learn her culture, language, and bond with her twin sister, Shuangjie. Instead, the timing and terms of the reunion were controlled and delayed by the adoptive family’s wishes, with Demick deferring to them, a choice that; in my view, showed little consideration for the Chinese family’s pain and rights. I know it might sound crass to compare this to the case of Madeleine McCann, but it drives the point home, if a Western child had been abducted and later adopted abroad, there would be no question that an immediate reunion with the birth family would be demanded. The double standard here is hard to ignore. It’s crucial to understand that Esther wasn’t abandoned, she was snatched from her auntie’s arms. She was deeply loved and mourned by her birth family from the very moment she disappeared. This fact makes the ethical questions around the delayed reunion and control over the story even more painful, as it underscores the profound loss experienced by her family.

In the end, Daughters of the Bamboo Grove is a powerful read and opened my eyes to many harsh truths about China’s recent history and international adoption. But it left me wanting more direct voices from those who lived through it and a deeper reckoning with the complex, often painful ethics at the heart of the story.

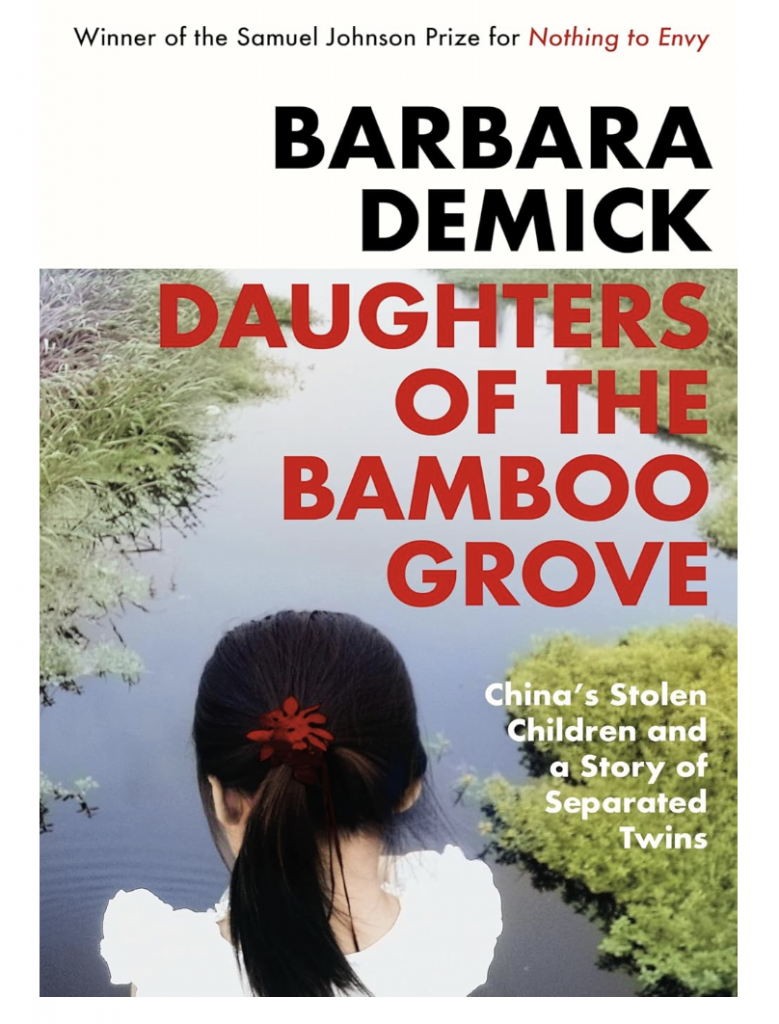

Featured image Sister by Chen Yifei

Leave a Reply