I’ve been thinking a lot about adaptation and how a story shifts depending on the medium, and how we shift, too, depending on when and how we encounter it. Recently I read The Boy with the Topknot by Sathnam Sanghera, then watched the TV adaptation. A few days later, I went to see Marriage Material at the Lyric Theatre, a play based on another of his books — this time doing it backwards: watching before reading.

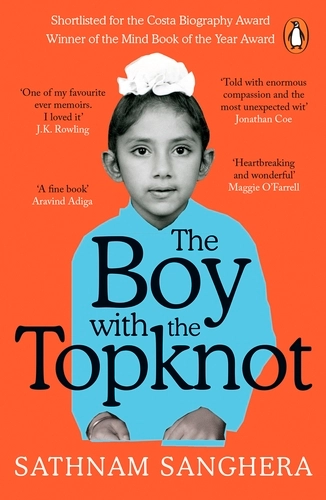

The Boy with the Topknot is Sathnam Sanghera’s memoir of growing up Sikhi in Wolverhampton, attending Cambridge, and later uncovering painful truths about his family’s struggles with mental illness. It’s an honest, sometimes uncomfortable look at race, class, family, and identity. Whilst reading I had complicated feelings about Sathnam who often comes across as a bit of an arse, trying hard to impress his white friends and distancing himself from other Sikhis by suggesting their interests didn’t match his. At times he was openly misogynistic, and even though he admitted it (“I know I sound misogynistic”), that self-awareness didn’t make it any easier to read. There’s a frustrating sense that he sees education and cultural “refinement” as somehow almost exclusively white or “English”— a feeling I’ve seen echoed among some Black people too— and used as an excuse for not having any Black or Asian friends (because “we have nothing in common!!! I like to read”) which never fully rings true to me. That being said this came out in 2009 and since then Sathnam has written Empireland, so potentially he’s already unpacked this. Still, the book is good, especially in its depiction of mental health. Sathnam’s discovery that his father and sister are schizophrenic — something hidden from him throughout his happy, sheltered childhood — is heartbreaking. He captures beautifully how families create their own mythologies: memories that shift with retelling and truths that depend on where you stood at the time. One moving moment is when his sister remembers him hugging her in hospital with love so strong she never forgot it — while he barely remembers the visit at all.

After reading the book, I watched the TV adaptation and honestly, it left me a bit cold. It wasn’t bad, exactly, but it flattened what made the memoir so emotionally and structurally interesting. The show reframes Sathnam’s story as a gentle romantic drama, with a likeable but awkward protagonist, a cheeky tone, a white girlfriend he’s reluctant to introduce to his traditional Sikhi family. A big part of the problem is the format. It was made as a 90-minute TV film, and you can feel how that limitation squeezes the story into a neat, watchable arc. But The Boy with the Topknot isn’t neat. It’s about shifting memories, competing truths, and the slow, painful unraveling of what you thought you knew. A lot of that gets lost when you’re working with such a short runtime — there just isn’t space for all the nuance, all the silences the book sits with so powerfully. The book is anything but linear. It’s shaped by fragmentation — by what isn’t said, by memory gaps, by unreliable narrators within the family and even the emotional unreliability of Sathnam’s own recollections. It’s not just a story about discovering a hidden family truth — it’s about realising that your whole memory of your upbringing might not be as solid as you thought. And that realisation doesn’t come in one dramatic moment — it creeps in slowly. As the eldest in my own family, there are moments I remember clearly that my younger sister doesn’t at all. Not because they didn’t happen, but because we experienced them from completely different places. Our ages gave us different access to meaning. Memory is never evenly distributed, especially in families. This should’ve been a mini-series. The material demands more time, more air — not just to represent the story accurately, but to honour the complexity of it. Mental illness, intergenerational trauma, cultural identity, class aspiration, self-erasure — none of that fits cleanly into a rom-com-adjacent structure. And the memoir isn’t about “opening up” in a single moment. It’s about the much slower, lonelier work of realising how much has been hidden but also how much you’ve hidden from yourself.

It’s hard not to wonder why this story, with its richness and cultural specificity was given only a 90-minute slot. Would a white British memoir tackling mental illness, class, and family trauma be so neatly packaged? Or is this a symptom of how mainstream British TV often treats stories by people of colour, especially when they’re deeply personal, as only worth telling if they’re also easily palatable? The adaptation leans heavily into the “brown boy meets white girl” framing, as if anchoring the story in a familiar interracial romance makes it more digestible for a presumed white audience. That choice feels like a concession: a narrative structure that softens the political and emotional sharpness of the book to fit a gaze that still sees South Asian family life as something to be explained rather than inhabited. Perhaps a better example of what’s possible can be seen in the recent adaptation of Bernardine Evaristo’s Mr Loverman, which unfolds over eight half-hour episodes. The show explores Black British masculinity, ageing, queerness, and love, themes that are often underrepresented on screen and it does so with tenderness, complexity, and humour. Crucially, it’s given the time to breathe. The longer format allows for nuance: shifts in memory, tensions between generations, and the emotional weight of secrets carried over decades. It’s a reminder that stories grounded in cultural specificity, especially those by writers of colour, don’t need to be trimmed down to be accessible. They flourish when they’re allowed depth.

I saw Marriage Material at the Lyric Hammersmith before reading the novel, and I think the play, adapted by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti was actually more successful than the book. Interestingly, it may have worked because it left us outside the main character’s head. Without the main character Arjan’s internal monologue (which, in the novel, often felt smug and self-regarding in a way that recalled Sathnam’s voice in The Boy with the Topknot), the story was freer to open up to the ensemble cast around him. In the book, the sisters were written in third person and felt frustratingly peripheral; on stage, they came alive. The play gave space to a range of perspectives and didn’t feel so tightly bound to Arjan’s self-image — or his self-deprecating but still somewhat self-congratulatory tone. It also helped that the story unfolded through dialogue and staging, rather than narration, which made its tensions feel more lived-in and less explained. Like the memoir, the novel was preoccupied with perspective — who gets to tell the story and how — but the play showed how liberating it can be when we step outside one character’s gaze. In that sense, it felt more communal, more layered, and crucially, more emotionally resonant than the source material.

What was fascinating, though, was comparing how certain tensions played out differently in the novel versus the stage. In the play, for instance, it wasn’t entirely clear why Tanvir would be seen as such a bad match for Kamaljit — aside from him being a bit dopey. But in the novel, the stakes are made more explicit: Tanvir is a Chamar and Kamaljit is Jat, and the caste difference is treated by the community as a scandal on par with Surinder running off with a white man. This added detail deepened my understanding of the social dynamics at play. The book also gave more insight into why someone like Tanvir might want to move beyond inherited tradition, whereas someone like Dhanda was invested in recreating a “little India” in Wolverhampton. These layers — caste, migration, generational change — were much sharper in the novel, even if the reading experience itself was sometimes a bit of a slog.

Reading about caste made me think more broadly about how certain hierarchies survive migration by reshaping themselves. I recently read Partition Voices by Kavita Puri for my book club, a non-fiction book that documents the oral history of people who lived through the 1947 Partition of India in a series of interviews. It’s an incredibly moving archive of testimony that aims to preserve memories often excluded from official British histories. It was observed during our book club discussion that most of the people interviewed had, in one way or another, “made it” in Britain. They had become doctors, teachers, business owners — people whose stories of Partition were also tied to narratives of resilience and success. And it made us wonder: who gets invited to tell their story? After reading Marriage Material, I also wonder, could caste have played a role in that? Even if caste isn’t mentioned explicitly, was it shaping which stories were seen as representative or respectable enough to include? In Marriage Material, caste isn’t always foregrounded, but once it’s named, it reconfigures everything. Tanvir is Chamar; Kamaljit is Jat. For generations, his family worked for hers, and even in the UK — supposedly far from the rigid structures of rural Punjab — that social hierarchy is reproduced. Tanvir becomes their shop boy and sleeps on the floor of their stockroom. Their relationship is only sanctioned when the family is publicly disgraced by Kamaljit’s sister Surinder running away with a white man. Kamaljit, already viewed as the “less desirable” sister, is left with few options — and her marriage to Tanvir is treated as a tragic concession. This echoes how caste structures can persist silently, shaping not only who people marry but also what kinds of lives are imagined as desirable or successful. In Tanvir’s case, his rejection of inherited tradition isn’t just youthful rebellion — it’s a refusal to be slotted back into a system that defines him by ancestry. And in Dhanda’s desire to recreate a “little India” in Wolverhampton, there’s more than nostalgia: there’s a need to preserve a version of home in which those hierarchies remain intact.

Perhaps caste also subtly shapes the different trajectories expected of the younger generation. In the novel, Tanvir pushes his son Arjan to become a doctor — a prestigious, socially mobile profession that would have been unimaginable for someone of his caste in India. For Tanvir, migration also represents a break with inherited limits, and education is the vehicle for transcendence. By contrast, Dhanda expects his son Ranjit to take over the family business, not out of lack of ambition but because as Jats, they already possess a kind of implicit social status. For them, respect isn’t something to be earned through qualifications; it’s assumed. This contrast reveals how caste continues to shape aspirations in the diaspora, not just in terms of what’s possible, but in terms of what’s seen as necessary. It’s a dynamic echoed across many migrant communities — where class, caste, or race intersect with different ideas of success and survival. Even at the end of The Boy with the Topknot, Sathnam’s mother casually remarks that it would be better if he married a Christian or a Muslim than a Chamar. At the time, this line didn’t really register with me — it felt like just another passing comment. But after reading Marriage Material, its significance became much clearer. Sathnam is a Jat, and so caste isn’t the central focus of his memoir in the way it is in Marriage Material. While Sathnam feels the pressure of class in how his family expects him to marry within their Jat caste, he doesn’t fully grasp the significance of caste the way someone from a Chamar background might. As Sathnam himself remarks, he knows they are “different,” but he doesn’t quite understand the deep social weight behind that difference. This is often the way: those in dominant or higher caste positions may recognise difference but remain unaware of its full impact, while those from lower castes live it daily, experiencing discrimination and exclusion firsthand. Both The Boy with the Topknot and Marriage Material were published over a decade ago, so it’s natural that Sathnam Sanghera’s perspective has evolved since then. His later work, Empireland, tackles issues of caste, class, and identity in even greater depth, showing how these themes continue to shape British South Asian experiences and his own understanding. This progression highlights how complex social structures like caste don’t just disappear but require ongoing reflection and unpacking over time.

Coming to the book after seeing the play also shaped how I received it. Having already watched the story performed, the novel often felt less emotionally immediate and more like a history lesson — not in a dry way, but in the sense that it filled in cultural and social context the stage version had to leave out. The details about caste, migration, and community politics deepened my understanding, even if they didn’t always make for the most fluid reading experience. It reminded me how performance can draw us in emotionally, while prose can sit us down and explain the weight of what we’re watching — and both have value. But it also showed me how much more powerful a story can be when given the space to unfold fully, across multiple forms. Thinking about both The Boy with the Topknot and Marriage Material, what strikes me is how each medium reshapes the emotional centre of the story. Where the TV adaptation of Topknot diluted the book’s complexity in favour of a simplified romantic plot, the Marriage Material play gained power by decentralising the narrator and allowing other voices to breathe. Ultimately, what these experiences have shown me is that adaptation is never just about transferring a story from one form to another — it’s about re-encountering it. It’s a reminder that adaptations don’t just reflect a story — they reimagine its gravity. And maybe that’s what I’ve been circling all along: stories aren’t fixed. They change depending on who tells them, how they’re told, and who’s listening. And so do we.

Leave a Reply