In his essay collection Delight, JB Priestley explores a variety of delightful things. It’s remarkable how ridiculously specific and yet deeply resonant many of these delights are. I’d not previously thought about the delight of “drinking mineral water in a foreign hotel,” but come to think of it—it truly is when water tastes its most refreshing, especially after a long day of exploring, like me; Priestley also takes delight in a walking tour. I also love the one about cosily reading in bed when it’s pissing it down outside, only made all the more delightful when it’s also pissing it down in the book. It reminded me of a personal delight from when I taught primary school. Being a teacher is often stressful, and we teachers do love a moan – but it’s also sometimes genuinely delightful. I remember rare occasions when, having got all our boring book work done in the morning, we’d spend the afternoon drawing while listening to an audiobook (The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe maybe, or When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit by Judith Kerr). On those days, it would often feel like the whole class had silently decided to be on their very best behaviour, as if under a spell (a good story will do that.) I remember this always being all the more delightful when you could hear the rain tapping dancing on the roof of the classroom. I think my favourite essay from the book is the one about playing chamber music at home (I liked it so much that I photocopied it and stuck it in my diary.) I work at a conservatoire, a place where people tend to take music extremely seriously (almost comically so at times.) Priestly writes about the ‘cosy magic’ of playing music together with friends ‘we forget’ he writes ‘that a lot of music has been written for fun.’ So dust off the piano, let the wine flow and remember that despite the fact you’re only playing about half the notes (and often in the wrong order) that, ‘Mozart and Haydn, Brahms and Debussy, move among us again; and within the ring of friendly faces, ghosts these many years, the little worlds of sound shine and revolve like enchanted moons.’

Like me, Priestley liked a good grumble. In the introduction to Delight, he moans about post-war austerity and how the government wasn’t doing enough to promote fun. I get it – living through a cost of living crisis is pretty shit and I too spend a lot of time having a whinge. Ross Gay’s collection The Book of Delight, doesn’t tackle delight in the same nostalgic way as Priestly but as a radical, attentive practice. Gay’s essays uncover joy in the ordinary and overlooked, his delight is political, tender, and fiercely present, rooted in Black joy, vulnerability, and the simple act of noticing. I loved how present both Priestley and Gay’s writing feels. It made me notice more in my own life too, like how a class of normally rambunctious children drawing quietly to an audiobook on a rainy afternoon is its own kind of magic. Or how playing music with friends, albeit badly, can feel just as important as playing perfectly. Both Gay and Priestley reminded me that delight isn’t about escaping the world, it’s about paying closer attention to it.

When Life Gives You Tangerines

There’s something endlessly satisfying about diving in to a good family saga, the kind of story that spans generations and is filled with the mythology of family life. Most of my favourite books are from this genre, Family Lexicon, Wild Swans , Pachinko, and The Joy Luck Club to name a few. Who can deny the delight of becoming lost in a tapestry of characters stitched together by blood, history, and circumstance, of unspoken rivalries, fierce loyalties and inherited traumas, the way a grandmother’s decision in 1930 can ripple forward through time and affect a great-granddaughter’s fate, the full circle moments of life. These stories offer more than just the intimate drama of family life but can also become a lens through which we understand history. The personal is inseparable from the political, as characters live through war, migration, and cultural upheaval. These stories root historical events in the everyday and show how the weight of history is felt not only through newspaper headlines, but in the inherited fears, hopes, and language of a family. I also have a soft spot for soaps, which, when you think about it, are just family sagas in daily doses. There’s comfort in these stories, and a kind of catharsis too. They remind us that even though life is so often chaotic and heartbreaking, there is a continuity and rhythm.

When Life Gives You Tangerines is a poignant and richly layered K-drama that captures the lives of multiple generations of a family. Set against the picturesque backdrop of Jeju Island and spanning decades the story follows Ae-sun and Gwan-sik from their childhood romance into old age, while also exploring the lives of their children and grandchildren. The series masterfully weaves together past and present, showing how each generation inherits not just traditions and values, but also wounds. It’s a heartfelt portrayal of how families grow, evolve, but remain deeply connected across time.

Field Work

There’s a particular delight in imagining the countryside when you live in the city, a wistful pleasure in picturing rolling hills, winding lanes, and the unhurried rhythm of rural life. It’s why I love watching All Creatures Great and Small, a tv show based on the books of the same name by James Heriott, set in the idyllic Yorkshire dales the stories charmingly present the daily rhythms of a rural veterinary practice. Whether it’s a scruffy dog getting patched up or a stubborn cow coaxed back to health, not much ever goes wrong that can’t be fixed with a cup of tea. Of course, it’s all an illusion. The countryside is no stranger to hardship. I recently read, Field Work by Bella Bathurst which explores the gritty, often unseen realities of rural life in Britain. Bathurst focusses particularly on the mental health struggles faced by farmers especially when so much of their livelihood is dependent on things as unpredictable as the weather. Through a mixture of storytelling and interviews, Bathurst reveals how isolation, financial pressure, and emotional burden weigh heavily on those who work the land. Many farming families have raised generations of animals from a continuous bloodlines for hundreds of years, which speaks to why it is so difficult to walk away, particularly for those who feel the overwhelming weight of legacy. I was particularly shocked reading about the devastation of the 2001 foot and mouth epidemic for this reason. The book challenges romanticised notions of the countryside, presenting a more nuanced and honest portrait of rural communities and the silent crises they endure. But in the city’s relentless noise and pace, the idea of the countryside becomes something else entirely: representing not only a place, but also an escape. It stands for space, stillness, and the comforting lie that somewhere, life moves slower, gentler, and more in tune with the seasons.

“She talked about sitting there in the straw for hours, stoned with tiredness, watching the ewes turning in the straw until their gaze reached inward and the time was right to plunge her hand into the tangle of legs, pulling the scrappy lambs into the world, knowing that she had drawn out the life inside. Just before dawn she would walk out of the shed on the hill and gaze up. In her memory it was always frosty, and the great velvet cosmos was always spread above her and the enchanted ground always glittered.” Field Work by Bella Bathurst

In the end, delight shows up in unexpected places, in familiar stories retold or quiet moments remembered, or in the way a soap opera can pull you into someone else’s world for a while. Whether it’s a windswept farm, a family living through history, or a music-filled living room, these stories offer small anchors. They serve as reminder to look a little closer, to take notice. And maybe that’s part of what I love about arts books places, the way art and stories keep nudging us to pay attention, to find joy tucked into the corners of everyday life.

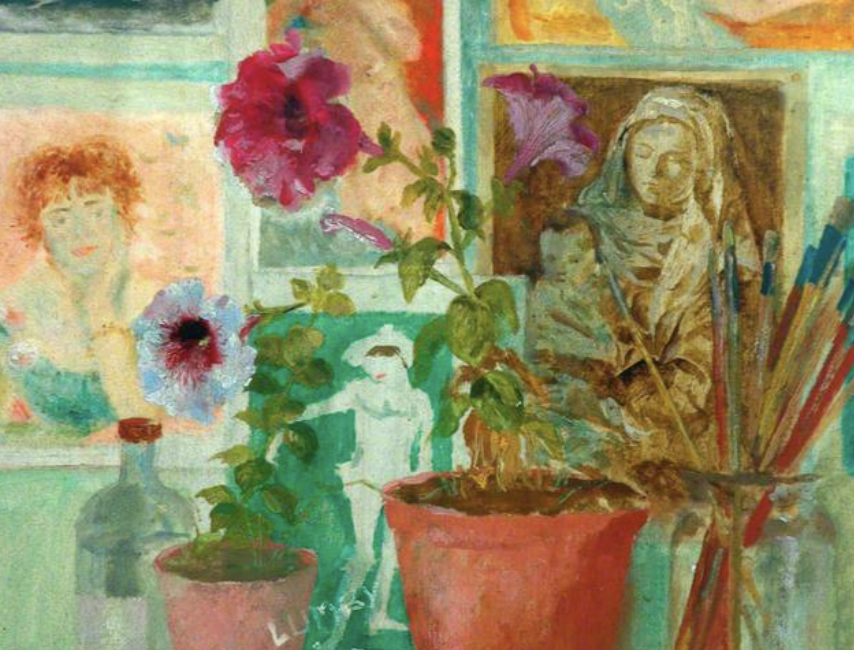

Featured image Studio Mantlepiece by James Fitton 1947

Leave a Reply