Growing up in London, once a year the school would take us to the National Gallery, where we would trudge through endless Madonnas and saints, half-asleep, just waiting for the when it was finally time to go to the gift shop. Let’s have it right, old museums are BORING. Honestly, it’s a miracle I managed to foster a love of art at all. For my sins, I graduated with a degree in the History of Art, which sounds very “Renaissance altarpiece” until I tell you I studied at Goldsmiths, where we spent more time on Dadaism and pouring over the SCUM Manifesto than we ever did on Madonnas and saints. My idea of a thrilling seminar was someone doing a shit in the middle of a crit, or arguing over whether two clocks on a wall count as art (they do and Félix González-Torres’s Perfect Lovers is perhaps one of the most moving works I’ve ever encountered).

Which is why the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna caught me off guard… It was Ferragosto, the city shuttered and empty, the streets unbearably hot and frankly I was fed up with how quiet things were (having not done my research, I didn’t realise that Bologna basically shut up shop for the last 2 weeks of August.) However, when I stepped inside the museum, the emptiness gave it a mythical quality, like I’d slipped into another layer of the city, one reserved only for me and the paintings. And thank goodness, there was air con!!!!!

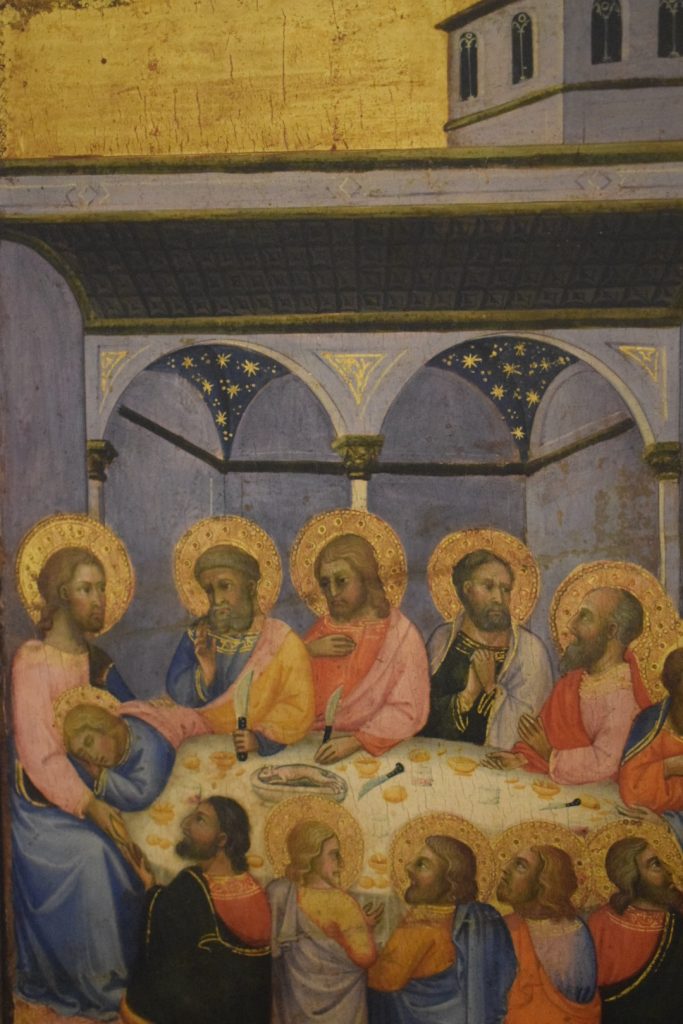

Honestly, the pieces I loved weren’t the big famous ones. Forget the Massacre of the Innocents or the austere paintings of noblewomen. II was drawn to the tiny, ridiculous corners: a presumably otherwise naked man with wavy gray hair trailing down to his ankles; Jesus lounging on Mary’s lap like the diva he is; a Last Supper with a laughably paltry offering that could be a rat; and men in white robes sneaking up a ladder to heaven, clearly leaving behind a friend who didn’t get the memo and is taking a kip. These little absurdities made me laugh, but they also made me feel strangely connected to the people who painted them. The medieval humans who painted these pieces are long gone, yet somehow still present in the brushstrokes and quirks. Medieval art has a long tradition of this kind of absurdity; the closer you look, the more personality peeks through the piety and gold leaf.

The next day I took the train to Ravenna and (I can hardly believe I’m writing this) spent the day touring churches. Churches! Something must have possessed me, because generally I think most old churches blur into one: high ceilings, stained glass and a faintly musty smell. If you’ve seen one, you’ve basically seen them all. Not that I don’t like an old church, I do and on occasion, Christmas, Easter, Ash Wednesday, Epiphany, or when something so terrible has happened I have nowhere else to turn (being ever the fair-weather Christian) I will pop into church. But if I’m going to go, I want a proper church, not a community centre, not a modern building, not a cinema or a megachurch. I want to feel the weight of history and the faint smell of incense and stone. I think it’s because I find church comforting more for the aesthetics than the word. The familiar architecture, the way the light falls on the altar, the formulaic rhythm of the Eucharist, all of it has a quietly reassuring pattern.

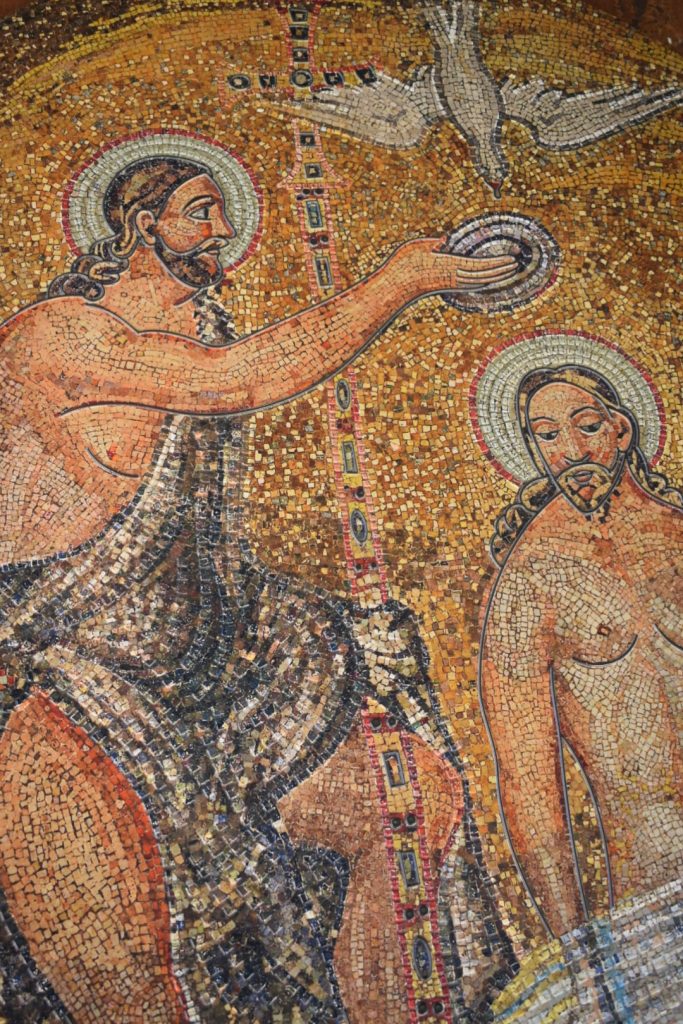

But I went to Ravenna for the mosaics, shimmering gold and jewel-bright, like the walls were trying to outdo heaven itself. And I’ll admit it, I also went because churches are cool inside, and after two days of being roasted alive in Emilia-Romagna, I was desperate for shade. And yes, I paid €13 for the privilege. Although, many famous churches now charge entry, St. Paul’s in London, for example, and even some Vatican sites so Ravenna isn’t unique in this.

What struck me most was the silence, these churches serve more as monuments than places of worship. No incense, no murmurs of prayer, just tourists padding around and staring upwards. It’s a strange contrast to the Vatican in Rome, which feels alive in a way that Ravenna doesn’t, buzzing with prayers, music and ritual. And yet, the mosaics glowed so fiercely in the dim light that I forgot what was missing.

Here, unlike Bologna, I was struck by sheer beauty rather than absurdity. Each tessera placed with meticulous care, each pattern deliberate, each hand that worked on them long gone yet somehow present. I felt connected across centuries, to the people who made the work, to their devotion, their skill, their care.

Leave a Reply