Like many readers, I’ve come to terms with a difficult truth: I don’t live in a palace. My ceilings aren’t high, my shelves aren’t infinite, and while I love books, I simply can’t keep them all. So lately, I’ve been working steadily through my unread stack, reading, reflecting and perhaps most importantly… letting go. I’ve made the conscious decision to not let books pile up by making peace with the fact that I don’t have to keep every book I read. In fact, now I only hold on to the ones I truly love and the rest? They move on to new homes. I donate them to charity shops, stock the little free libraries at work and at the gym, or palm them off on friends. I recently also dipped my toe into the world of reselling and listed a couple of books on Vinted which was a bit of an experiment. After selling two books and making about three quid (not counting the cost of packaging and postage), I realised the effort absolutely outweighed the gain. What’s perhaps been most liberating is learning to let go of books I haven’t even read. For a long time, those unread titles came with a strange sense of guilt, like unfinished homework. But I’ve come to understand that just because a book made it onto my shelf doesn’t mean it has to stay there. Interests shift, timing changes, and not every book is meant for every reader. Letting go of them isn’t failure—it’s freedom.

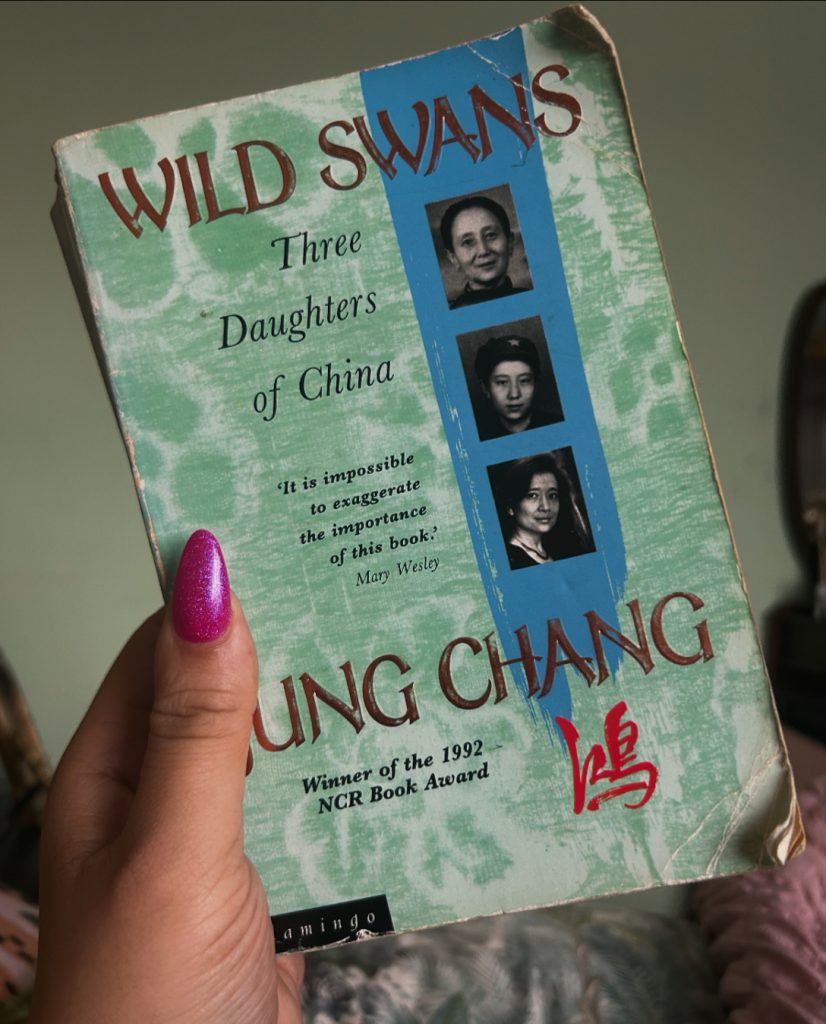

Take Wild Swans by Jung Chang, for example. I had owned it for years and actively avoided it—not because I wasn’t interested, but because, let’s be honest, it’s a bit of a chunk. I’d pick it up, admire the weight of its history and ambition (not to mention it’s physical weight, it’s like 700 pages), and quietly put it back. But this year, I finally dove in. Published in 1991, Wild Swans tells the story of China in the 20th century through three generations of women: Jung Chang, her mother De-hong, and her grandmother Yu-fang. While reading, I didn’t just step into a family’s history; I found myself swept into the bloodstream of a nation’s violent transformation. From the grandmother with bound feet who became a warlord’s concubine, to the daughter who marched miles for the Communist Party, to Jung Chang’s own disillusionment and eventual exile—each story felt like a window into both personal and political upheaval. One thing that really struck me was how different kinds of people ended up supporting the revolution. Peasants who had nothing left to lose, yes, but also educated idealists like De-hong, who genuinely believed they were building a better world. Jung Chang’s father is perhaps the most fascinating figure in the book. He grew up in extreme poverty but was also literate and intellectually curious. He could empathise with the peasants’ desperation, but he also believed deeply in the power of political theory and cultural reform. In many ways, he lived between two worlds: the oppressed and the intellectual. His idealism made him admirable, but his rigid Party loyalty made him hard to love. Still, there were moments—subtle, fleeting—where his humanity cracked through. And that’s what made him so tragic. A man torn between duty and love, in a world that punished both. Wild Swans isn’t just a chronicle of China’s political history. It’s about real people swept along by history. It’s about how revolutions, no matter how noble they start, come with unimaginable costs. And, in the end, it’s about the lives that are shaped, broken, and rebuilt by those forces.

And yes, after all that, I’ve decided to keep Wild Swans. It’s one of the few that earned its place on my shelf—proof that sometimes, even the books you avoid for years have something powerful to offer when the time is finally right.

Leave a Reply