Back in November 2024, I set out with modest ambitions: to mood-read my way through Nonfiction November. For the uninitiated, mood reading is the practice of picking up whatever appeals to you in the moment and just as crucially, putting it down when it no longer does. It embraces DNF’ing books with zero guilt, and fully supports spending a few days (or weeks) watching Love Is Blind instead. Honestly, it was the perfect way to get back into the rhythm of reading. Writing, though? A bit harder. Which is why you’re reading this in May 2025. Still, I’m calling it a win.

Queer as Folklore

By Sacha Coward

A campy, footnote-laced gateway drug to queer mythology

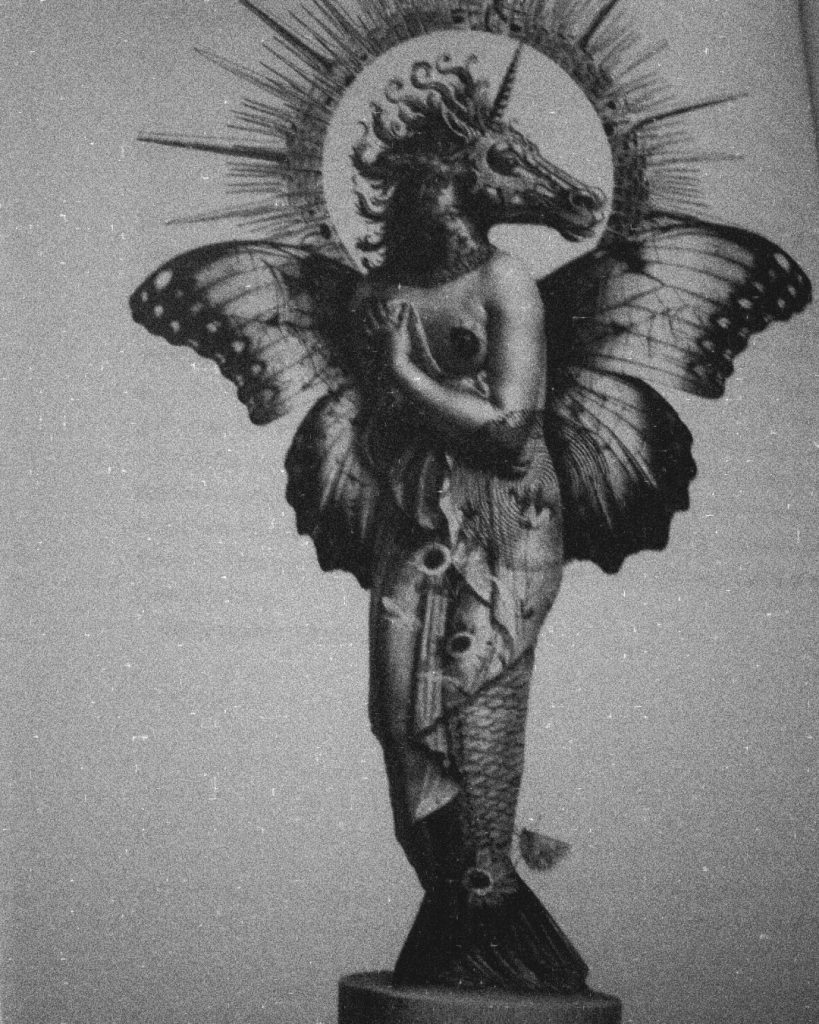

‘Queer as Folklore takes readers across centuries and continents to reveal the unsung heroes and villains of storytelling, magic and fantasy. Featuring images from archives, galleries and museums around the world, each chapter investigates the queer history of different mythic and folkloric characters, both old and new.Leaving no headstone unturned, Sacha Coward will take you on a wild ride through the night from ancient Greece to the main stage of RuPaul’s Drag Race, visiting cross-dressing pirates, radical fairies and the graves of the ‘queerly departed’ along the way. Queer communities have often sought refuge in the shadows, found kinship in the in-between and created safe spaces in underworlds; but these forgotten narratives tell stories of remarkable resilience that deserve to be heard.‘

I walk past Atlantis, London’s oldest occult bookshop, every week on my way to Italian class, but I’d never actually stepped inside. I’m not particularly witchy, and to be honest, I try not to mess with the occult unless absolutely necessary. But when I saw the cover of Queer as Folklore in the window, something about it pulled me in.

The book turned out to be a joyful, sprawling romp through the queer undercurrents of folklore and myth. Mermaids, werewolves, fairies, witches, demons, superheroes, pirates — no stone is left un-gayed. Most of the stories are drawn from Western mythology, which may disappoint some readers hoping for broader cultural representation, but Coward addresses this in the introduction where he admits there are people better versed to write more expansively from a non western perspective. Coward’s tone is witty, conspiratorial, and peppered with fascinating tangents (plus brilliant footnotes if you love a research spiral). If you’re even vaguely folklore-curious, this is a brilliant entry point.

The first chapter, on mermaids, sent me on a deep dive (no pun intended) into the life of Howard Ashman, the lyricist behind The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and Little Shop of Horrors. I ended up watching the touching Disney+ documentary Howard, which I highly recommend. Ashman, who died of AIDS-related illness in 1991, was a creative force behind some of Disney’s most iconic works and it was his idea to base Ursula on the drag queen Divine. A win for the gays, and for high-femme villainy. And once you start noticing it, you realise how many Disney villains are deliciously queer-coded: Ursula, obviously, but also Scar, Hades, Captain Hook, Cruella, Jafar… the list goes on.

Coward is also thoughtful in how he handles his sources and interpretations. He doesn’t sugarcoat queer history, and he makes a point of explaining why he interprets certain figures or myths as queer, while also offering alternate readings. That transparency felt generous. If you already know a lot about queer folklore, you might find this a bit surface-level. But if you love dipping your toes into lots of topics and following where your curiosity leads, it’s a treat.

Regarding the Pain of Others

By Susan Sontag

A slow, thorny reflection on images, violence, and spectatorship

‘What is the purpose of images of pain and suffering? Can there be any real justification for the creation, and consumption, of such images? In this seminal volume, Susan Sontag examines the uses and meanings of images, from inspiring dissent to fostering violence to creating apathy. And through this lens she considers the nature of war, the limits of sympathy, and the obligations of conscience.’

I hadn’t read Sontag in years, not since university, when Illness as Metaphor and On Photography were on my reading list. I remembered them vaguely, more for their presence in my dissertation bibliography than for their contents. But Regarding the Pain of Others pulled me in immediately.

Despite being written in 2003, its meditations on war photography, atrocity, empathy, and detachment feel just as urgent in the age of Instagram, Gaza, AI-generated images, and endless scrolling. I underlined endlessly and kept pausing to look up the photographs she referenced, which made this another very rabbit-hole-y read.

Sontag’s cool, incisive style can feel a little alienating at first, but I appreciated how it gave me space to think rather than just feel. I’ve since added the biography Sontag: Her Life and Work by Benjamin Moser to my TBR, it controversially won the Pulitzer in 2020 (note to self: find out what the controversy was!)

Crying in H Mart

By Michelle Zauner

A sensory, complicated memoir of grief, identity, and inheritance

‘In this story of family and food, grief and joy, Michelle Zauner proves herself far more than a dazzling singer, songwriter and guitarist. With humour and heart, she tells of growing up the only Asian-American kid at her school; of struggling with her mother’s expectations of her; of a painful adolescence; and of treasured months spent in her grandmother’s tiny apartment in Seoul, where she and her mother would bond, late at night, over heaped plates of food. But, as she grew up, her Koreanness began to feel ever more distant, even as she found the life she wanted to live. It was her mother’s diagnosis of terminal pancreatic cancer, when Michelle was twenty-five, that forced a reckoning with her identity and brought her to reclaim the gifts of taste, language, and history her mother had given her.’

I finally read Crying in H Mart after meaning to for years, and it hit me in ways I wasn’t entirely prepared for. It’s a memoir of grief, food, and mother-daughter relationships but also of cultural inheritance, fractured identity, and the weight of being an only child with a disappointing father. Zauner’s relationship with her mother is loving but intense; her father, meanwhile, feels like a ghost in the house even before her mother’s illness begins. There’s a section where she writes about his repeated affairs – private humiliations that had never even been spoken aloud between mother and daughter, that were suddenly made public in this book. I found myself bristling. To make something so private public, to me felt like a betrayal. I’m probably just projecting because I’m uncomfortable with that kind of vulnerability, having been brought up in a way that discourages the airing of ones dirty laundry. However, why should Michelle or her mum feel ashamed when it was her dad who done wrong?

There’s a powerful theme running through the book about language loss. As her mother grows sicker, she reverts more and more to Korean, and Zauner struggles to understand. A friend of her mother’s steps in to help, but instead becomes a kind of emotional wedge by refusing to teach Zauner recipes and mediating communication imperfectly. When the people who connect you to a culture are gone, what’s left? Can you still claim it or does it slip through your fingers?

I also kept thinking about how life isn’t like a movie. Sometimes the final trip doesn’t happen. Sometimes you run out of time. Sometimes secrets die with someone, and you’re just left with half-stories, missed chances, and untranslatable moments. Not everything gets said and not every ending is cinematic. And that’s part of what makes grief so prickly, the absence of closure, the things you’ll never know and the words you’ll never hear.

Her mother’s advice, to always keep 10% of herself, recurs throughout the book. There’s something heartbreaking about wondering whether some things shouldn’t be shared.

This ended up being a slow, tangled, non-linear Nonfiction November, which is to say, a very real one. I followed my instincts, let books lead me to other books and films and songs, and tried not to punish myself for reading (or writing) slowly. And if it’s May now? That’s fine. Because nonfiction, like folklore, like grief, like memory, like life itself, doesn’t always follow a neat timeline.

Leave a Reply