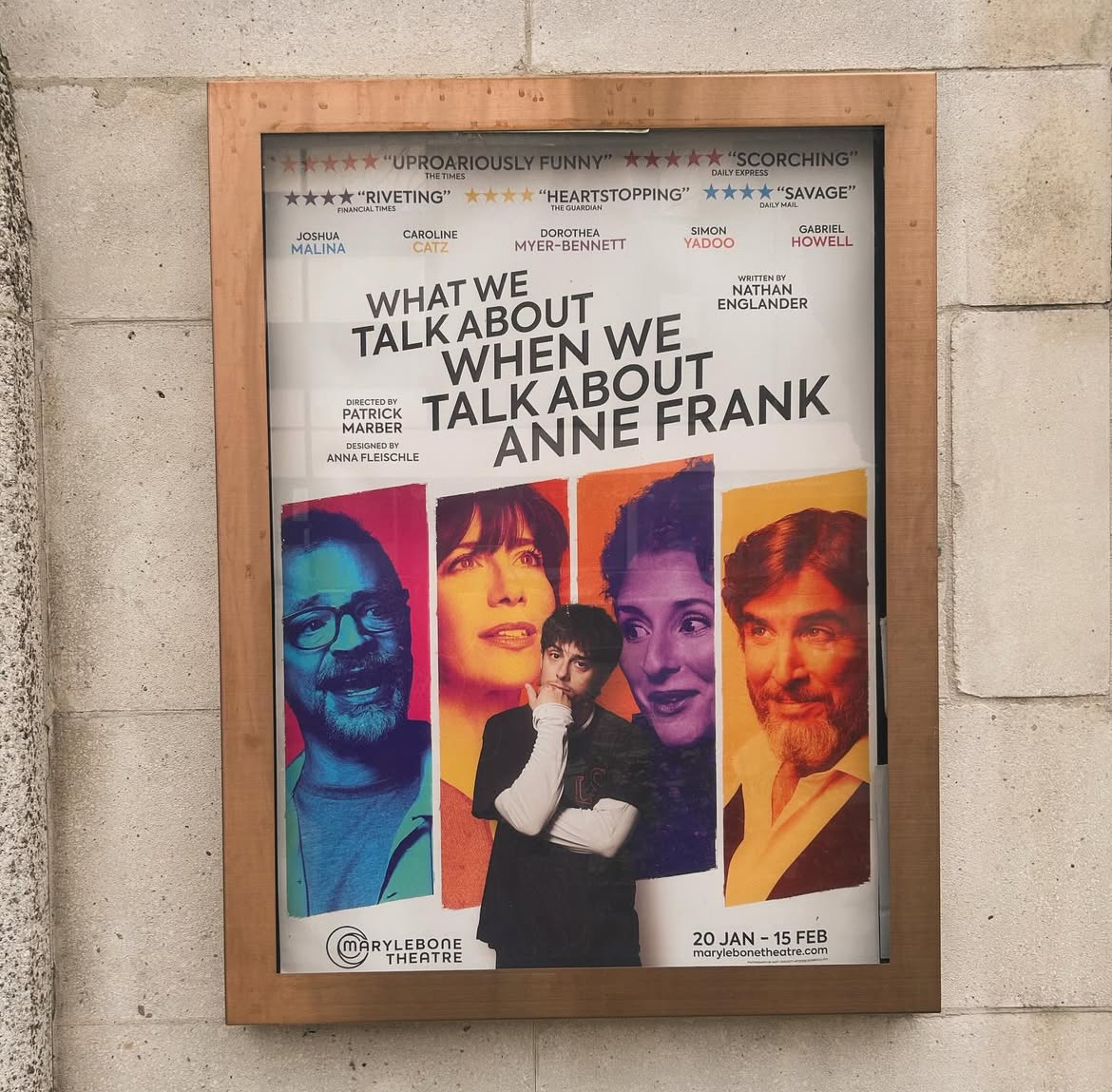

What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank

In February I took an impromptu trip to the Marleybone Theatre (very ‘off Broadway’ vibes) to see ‘What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank‘ There’s a trigger warning as you walk in explaining that the play contains discussions of war, genocide, religious/political violence, rape, kidnapping, arranged marriage, parental abandonment, drug use, alcohol, sex, language and physical violence (so all the bad things then) that being said… it was quite funny. It was also very thought provoking and confronting. The show presents two Jewish couples, one orthodox and one secular. The dialogue is based on the short story by Nathan Englander of the same name but has been adapted to reflect the times we live in e.g. ‘please don’t mention the war or the ceasefire.’ (this was just after the short lived ceasefire at the end of Jan) So the dialogue is constantly changing and adapting. I liked how the play presented two Jewish couples with completely different perspectives e.g. there’s a part in the play where they talk about the Holocaust and the couples have completely different relationships to it informed by their own experiences. The couple more removed from it, whose grandparents were born in Brooklyn seem to be more effected by the tragedy. Whereas the children of the survivors less so, remarking that the real Holocaust is intermarriage. The consensus is that the former, as secular Jews hold onto the tragedy of the Holocaust as a tangible thing that makes them feel Jewish. One of the couples are Zionist occupiers in Israel and I think the play does a good job of presenting Zionism as a response to anti semitism, whereas the other couple refuse to ever visit the Holy Land, comparing it to Apartheid South Africa.

The only part of the play that didn’t quite land for me was the son’s commentary, he appears half way through and offers what I think is supposed to be a gen z perspective. At one point suggesting that the Palestinian genocide isn’t really about religion, history, or nationalism, but about resource scarcity caused by climate change: that the land is only contested because otherwise we’d have to admit there isn’t enough to go around. To me this perspective falls flat, not because it’s entirely untrue, but because it’s so detached from the reality of the conflict. When homes are being flattened and people are being starved and bombed, it feels inappropriate to compress those experiences into an abstract thought experiment or a metaphor for broader systemic failures like the climate crises. In her essay, Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag talks about how people use metaphor to turn something painfully real, like cancer or tuberculosis, into something poetic, symbolic, or philosophical. She insists this metaphorical thinking distorts suffering and distracts from the material reality of what people are actually enduring. You could argue the same dynamic is at play with the son’s climate change comment, he turns a specific, violent conflict, with deep historical, cultural, and emotional stakes, into a metaphor for something else: global scarcity, ecological collapse, human selfishness. Of course, there’s also a counterpoint. Maybe his refusal to engage with the conflict on its historical or emotional terms is actually a generational reckoning that is shaped less by inherited trauma and more by global collapse. His comment about climate change and scarcity might not land emotionally, but perhaps that’s the point. It’s not about emotion. It’s about systems. In this reading, he’s not trivialising the conflict, he’s reframing it, by refusing to see it as exceptional. Suggesting, maybe, that all struggles over land, identity, and survival are the same. That ideology might be the language of war, but scarcity is the fuel. From this angle, the son is not dismissing the war, but insisting that we see it not as a closed moral debate, but as part of a larger, global crisis that demands a new way of thinking. However, I’m not sure this entirely redeems the hollowness of the moment. Even if everything is connected, we don’t need to theorise that in the middle of a very real lived pain. There’s a time for theorising and a time to shut up and bear witness to mass suffering. It makes me think of Jesse Eisenberg’s movie A Real Pain, which I saw not long after. It follows two American cousins retracing their family’s Holocaust history in Poland, both desperately trying to feel something. The film is awkward and funny and sad but it resists the urge to turn trauma into metaphor. What it captures instead is how grief doesn’t always make us better, sometimes it just makes us worse. There’s a part in the film when they’re on the Holocaust memorial tour, as the guide reels off fact after fact at the group, you can see David played by Kieran Culkin becoming increasingly agitated. It’s not that he doesn’t care about the facts. It’s that they’re being delivered with such cold precision that the experience starts to feel like a history lesson where the guide is trying to demonstrate his depth of knowledge on the Holocaust, rather than a reckoning with human loss. At one point, David basically asks, “Why haven’t we met any Polish people?” What he’s pushing back against isn’t the information itself, it’s the emotional sterility and the disconnection between historical information and lived experience. What he’s crying out for is space to actually feel something. That rupture mirrors the discomfort in the play when abstract political or environmental commentary interrupts more grounded emotional truth.

On my way out of the theatre I picked up Nathan Englander’s short story collection. It’s been a while since I’ve read the book and I’ve since given it away but the only story that really stayed with me from the collection is Sister Hills. Set in an early West Bank settlement, Sister Hills is an unsettling and timely parable about the personal costs of ideology and the moral gymnastics people perform in the name of faith. The story follows two women who move to an illegal outpost in the occupied West Bank, stolen Palestinian land. One night, in desperation, a mother “sells” her daughter to her neighbour for one shekel, believing the symbolic act might protect the child from death. This a belief that comes from the ‘old country’, whilst the women claim Palestine as their ancestral home by invoking biblical birthright and other zionist mythologies to legitimise their actions, when crisis hits and a child is sick, they reach for Eastern European superstition, exposing themselves. One of the story’s most haunting symbols is the tree that one of woman attempts to cut down early on, an act that sparks confrontation with a Palestinian child who reminds her, she was not there when it was planted and if the tree is fell, it will be nothing but a curse on her bloodline. While the nation of Israel grows, the woman’s own world collapses. She loses her husband, her sons, and eventually shattered by grief she calls on the desperate, mystical exchange with her neighbour made all those years before. Her pain is real, and it’s immense. Englander doesn’t deny her that. But what the story makes chillingly clear is how that pain mutates into entitlement. Her grief doesn’t humanise her, it hardens her. She becomes convinced that her suffering has given her a kind of moral ownership, not just over a daughter, but over justice itself. She no longer sees the difference between superstition and law, between longing and theft. In part, Sister Hills is also about what it means to be Jewish in a world that has historically refused to let Jews feel at home. The women in the story are from Eastern Europe. Their customs, superstitions, and fears are shaped by the diaspora and by centuries of persecution, pogroms, and exile. The legacy of antisemitism has left them feeling unrooted, even in the places their families lived for generations. So instead, they cling to a mythic homeland, a place they’ve never known, but which offers them a kind of emotional certainty and historical absolution. This is the deeper tragedy of the story. The claim to Palestine isn’t always about domination for its own sake but comes from a place of deep longing desire to finally feel at home somewhere in a world that has repeatedly told Jews they don’t belong. But that longing, when left unexamined, becomes dangerous. Because in seeking to resolve their own displacement, these women end up displacing others. The story doesn’t accuse them but reveals them. And in doing so, it asks us to confront a devastating question: What do people do with generational trauma when they are finally given power?

Leave a Reply